Jean Cocteau’s Mediterranean period

Jean Cocteau, a “true Mediterranean” by adoption

In his youth, Jean Cocteau had already frequented the shores of the French Riviera in the interwar period, during more or less brief stays at Cap Martin, in Grasse, in Monte-Carlo, then in Villefranche-sur-Mer. But it was from 1950 that he settled there much more permanently. While shooting his film Les Enfants Terribles, Cocteau met an admirer, Francine Weisweiller, who immediately became his friend and patron. At her invitation, he stayed in the sumptuous villa she owned on Cap Ferrat, near Nice, then settled there for part of the year until his death in 1963. Cocteau, who lived all his life in the Paris region, felt he had become a “true Mediterranean.”

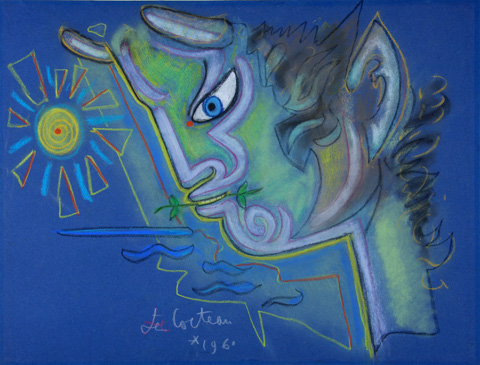

These years known as the “Santo Sospir period”, after his friend’s villa, marked a phase of intense creativity which led the poet to experiment with a multitude of new media. That period saw him dedicating himself in turn to wall decoration, easel painting, tapestry, pastels, ceramics, wax crayons and even the art of stained glass... Cocteau used all these means to explore colour, a clear departure from the use of black and white that had dominated his art until then.

A prolific “Mediterranean period”

But the Mediterranean influence can also be felt in the themes Cocteau dealt with. For him, all shores bathed by this sea “form a kind of homeland and the people who inhabit this homeland make up a family.” His stay on the French Riviera was an opportunity for him to reconnect with this seemingly inexhaustible source of inspiration.

First of all, Cocteau was interested in the mythologies originating from ancient civilisations bathed by the same sea on the shore of which he had settled. Graeco-Roman mythologies had been a major source of inspiration for the poet since he had set out to “retighten the skin of myths” in the 1920s through a very personal rewriting of the major motifs of Greek tragedy. But from 1950, it was mainly in graphic form that he continued to explore the lighter aspects of these themes, through series of drawings, notably his fauns, minor deities with goat’s horns, ears and hooves, who embody the exuberance of nature and eternal youth.

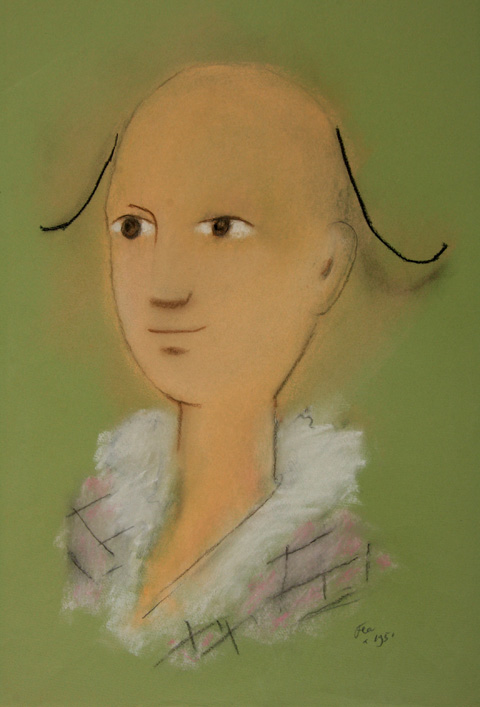

Other eminently Mediterranean themes inspired Cocteau, such as the characters of Commedia dell’arte, and in particular Harlequin, a character borrowed from Picasso’s pictorial world he made the subject of pastel drawings as well as a ceramic statuette. Furthermore, the famous Innamorati on display upstairs, although an original creation by Cocteau, also take their name, as well as their theatricality and sense of the grotesque, from Commedia dell’arte.

Spain is present through another theme inherited from Picasso, bullfighting scenes, which Cocteau drew alone or in collaboration with the young painter Raymond Moretti. Gitanos, introduced to him during a trip to the Iberian Peninsula, and who initiated him into the mystery of Flamenco, are also the subject of magnificent pastels.

Generally speaking, Cocteau’s Mediterranean years gave rise to an artistic production imbued with a certain joie de vivre, and his characters sometimes acquired a fish motif in place of an eye as an additional symbolic evocation of this inspiring sea.